John Gingerich on History of the Bernese Anabaptists: Interview and book giveaway

About four years back, Geauga County, Ohio native John Gingerich undertook to translate a text very important to the history of the Amish and other Anabaptists.

History of the Bernese Anabaptists was written by Ernst Müller and published in 1895. Up until now it has never been available in English.

History of the Bernese Anabaptists was written by Ernst Müller and published in 1895. Up until now it has never been available in English.

In today’s interview, John explains how the translation came about while offering a fascinating look at the story of this important group, including what made them different from other European Anabaptists.

John also discusses their influence on the Amish and other Anabaptist groups today. One of my favorite quotes on that point: “The Bernese Anabaptists were also noted for their hard-headedness. The Amish sometimes joke among themselves that they have inherited this trait!”

More importantly, the Christian martyr tradition of the Bernese Anabaptists lives on in their many descendants today. With the book now available in English a much wider audience will be able to access the story of their forbears.

History of the Bernese Anabaptists book giveaway

John has also kindly made a copy of the book available for giveaway. To participate, simply leave a question or comment on this post. The winner will be drawn one week from now, on Tuesday, July 12.

John has also kindly made a copy of the book available for giveaway. To participate, simply leave a question or comment on this post. The winner will be drawn one week from now, on Tuesday, July 12.

The book is also available for $10 plus shipping here, where you can also view more info on the book and sample pages.

John Gingerich on History of the Bernese Anabaptists

Amish America: What got you interested in writings on Swiss German Anabaptists?

John Gingerich: My father was raised in an Old Order Amish family in Geauga County, OH. Although he never joined the Church, most of the relatives on that side of the family still belong to the O.O. Amish, or related “plain” churches.

I’ve had an interest in history, especially family history and genealogy, ever since I was very young. I grew up hearing stories about such ancestors as Jacob Hochstettler, who was captured by the Indians, along with his two sons, during the French-Indian war in the 1750’s, and “Der Weis” Jonas Stutzman, another ancestor from Holmes County, OH, who always wore white clothing, as well as many other stories. In fact, I have a chair that was made by “Der Weis” Stutzman.

I soon realized that a person can’t have a good understanding their own family history without having some knowledge of the larger history and events, the context in which their forefathers lived. Thus, I became interested in Amish-Mennonite-Anabaptist history and read quite a bit of material on the subject.

When my last grandparent, Amanda (Schmucker) Gingerich, passed away in 1988, I was given some Testaments, hymnals and prayer books that had belonged to my grandparents and great-grandparents. This led to an interest in the literature of the group, and eventually I began collecting books relating to Amish-Mennonite history. In doing so, I formed many friendships with other book collectors, such as Leroy Beachy in Holmes County, OH, and David Luthy, director of the Old Order Amish Heritage Historical Library in Aylmer, Ontario. By the way, Leroy Beachy just completed his 20-year project, a fascinating, comprehensive book titled Unser Leit (Our People), documenting the history of the Amish.

David Luthy and I became very good friends, and he not only encouraged me in my book collecting endeavors, but we also engaged in many wide-ranging conversations about Amish-Mennonite history. It was during one of these conversations in Feb. 2007 that we had a discussion about the many books significant to Anabaptist history that were originally written in German but never translated into English. David mentioned that there had been a number of attempts over the past two decades to translate the book Geschichte der bernischen Täufer into English, but to no avail. This conversation inspired me to look into translating the book.

Can you share a bit about the importance of this text? How do Amish and other Anabaptists view it today?

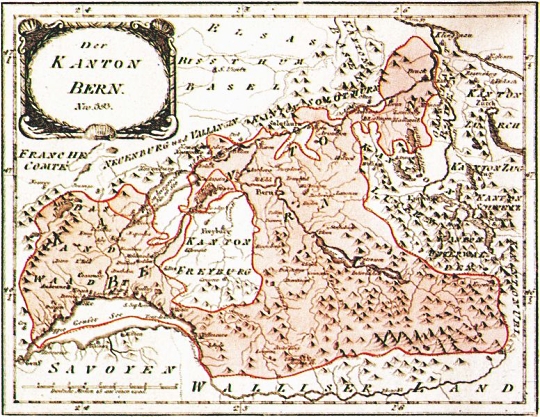

John Gingerich: This book is significant because it was the first extensive, objective portrayal of the Anabaptists of Canton Bern that had been written up to that point. Prior books about the group were largely written by their opponents. Since its publication in 1895, the book has frequently been referenced and cited by researchers and historians.

One example of how the book is viewed by Amish and Mennonites today is exemplified by Amos Hoover of the Muddy Creek Farm Library (which houses an extensive collection of documents and books significant to Anabaptist history), who wrote that this book is “the glue in putting our entire collection into one voice,” and he further felt regarding the translation that “there was no book put out in recent history which was so critical to our Swiss Anabaptist heritage.”

What kind of revelations, if any, did you come across that you were not previously aware of?

John Gingerich: I think what impressed me about the early stages of Anabaptism in Switzerland, at the beginning of the Reformation, was how it was such a time of religious experimentation. In freeing themselves from the Catholic Church-State, the early reformers had many discussions, or disputations, about interpretation and application of the Scriptures. Both those who would eventually be persecuted, as well as those who would be persecutors, gathered together to discuss such things as the nature of the Church, its relationship to the State, application of the ban (excommunication), etc. Müller states in his book that it wasn’t certain at one point in time if the Anabaptists wouldn’t actually become the dominant party. Ultimately, however, those in favor of infant baptism and the official State Church relationship dominated the argument.

It would be interesting to conjecture about what would have happened if the Anabaptist view of adult believer’s baptism, separation of Church and State, non-resistance, not swearing an oath, etc, would have held sway. I can think of many scenarios, which would be too much to put into this interview.

What sorts of challenges did Anabaptists in Europe face? Why was Anabaptism seen as a threat? And how did attitudes towards Anabaptists change over time?

John Gingerich: Right from the outset, they were subject to severe persecution, including imprisonment, exile, being sentenced to the galleys, torture, and execution. The rejection of infant baptism itself was viewed as a threat to the established Church-State order, for baptism at birth was not only viewed as joining one to the established Church, but also as one becoming a member of the community and obtaining citizen of the state. Swearing the oath of allegiance was a fundamental part of Swiss citizenship, and refusal to do so was viewed as an abdication of one’s duties to the Fatherland. In addition, not bearing arms, either in personal defense or in fighting for one’s country, was considered seditious.

Gradually, many European States began to allow the Amish and Mennonites to make an affirmation rather than give an oath, and to render some type of alternative service rather than take up arms. The Anabaptists, however, existed in a precarious state, because official toleration of them could change at any time.

The modern-day descendants of the Anabaptists also have a variety of views on these subjects. Although adult believer’s baptism continues to be a central doctrine, some churches no longer promote the principles of non-resistance or not swearing of an oath. Most conservative branches, however, continue to promote these beliefs.

We often read about how the Amish and Mennonites are admired by modern society for their religious, moral, and family values. The Amish were widely hailed for their beliefs about forgiveness after the Nickel Mines shootings.

However, we also recently experienced the other extreme of how their core beliefs are viewed by what happened at Goshen College in the past few months. Although this Mennonite college had quietly adhered to its Anabaptist principles for the past century of its existence, and thus did not play such patriotic songs such as The Star Spangled Banner at sporting events, it reversed this policy in 2010. This created a controversy among students, faculty, and alumni of Amish and Mennonite background. Subsequently, the school’s Board decided recently to revert to its original position, and said it would seek an alternative song.

This has created a national outcry and condemnation by many. No matter one’s position on the issue, I think a person has to understand the historical context in which the Amish, Mennonites, and other Anabaptist groups hold these beliefs. Our forefathers were willing to be imprisoned, tortured, exiled and, in some cases, executed, for these principles. Their strong belief in separation of Church and State, considered radical and traitorous in the 16th century, is now one of our fundamental American values.

Their willingness to nonviolently sacrifice their lives for these beliefs, in my opinion, takes as much courage as someone’s willingness to do the same while fighting for their country.

What distinguished the Bernese Anabaptists from others?

John Gingerich: Unlike Canton Zurich, which succeeded in virtually eradicating its Anabaptists through intense persecution, Canton Bern was never able to completely rid itself of the Anabaptists. In fact, the oldest “Taufgesinnten” Church, formed in 1530, still exists to this day in Canton Bern.

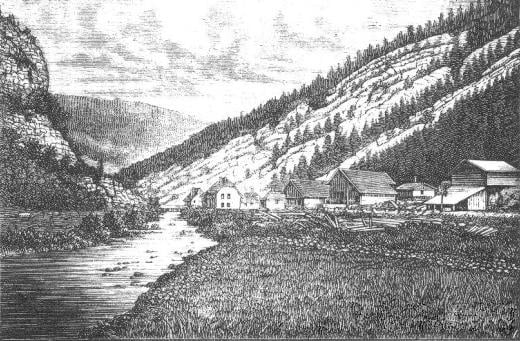

Although the Anabaptists in some areas were highly educated, Müller notes that the Anabaptists of Canton Bern were largely farmers and herders. Most people think of the Anabaptists of that era as being radicals, but Müller describes those in Bern as being ultra-conservative in their views. He felt their positions regarding the church, state, infant baptism, etc, reflected ancient beliefs, handed down from such “heretical” groups as the Waldensians. He noted that, at the time of the Reformation, they already possessed a well-developed theology and knowledge of Scripture. He asked how this could have been possible unless the group was already reflecting ancient, pre-Reformation beliefs? This view is rejected by most modern historians, but I’ll leave those arguments up to the academicians.

The Bernese Anabaptists were also noted for their hard-headedness. The Amish sometimes joke among themselves that they have inherited this trait!

What countries in Europe did Bernese Anabaptists inhabit? What remnants are there today?

John Gingerich: Because of intense persecution that lasted almost three centuries, the Anabaptists of cantons Zurich and Bern were forced into exile, sometimes individually and sometimes en masse. They then migrated throughout Europe, into such locales as Alsace and Lorraine (modern-day France), Moravia (portions of modern-day Poland, Czech Republic and Austria), along the Rhine River in modern-day Germany, the Netherlands, and even into Russia and modern-day Romania (with the Hutterites).

Although the last Amish Church in Europe ceased independent operations in the 1930’s, Bernese Anabaptist ancestry can still be fond in Mennonite congregations in France, Germany, and the Netherlands and, of course, in Switzerland.

Chapter 15 is entitled “Foiled Deportation to America”. I think many picture the migration of Anabaptists to America as that of a persecuted people willingly seeking a land of religious and economic freedom. When were Anabaptists under threat of deportation to America, and why did they resist?

John Gingerich: It’s important to remember that, despite all persecutions experienced, the Anabaptists loved their Swiss homeland. When exiled, many returned under the threat of being “sentenced to death or lifelong imprisonment or, ultimately, condemned to the galleys.” By the end of the 17th century the authorities in Canton Bern felt very frustrated about their inability to rid themselves of these “Taufgesinnten” (baptism-minded, i.e., those believing in adult baptism). Therefore, they sought other, more effective means.

In 1699, they communicated with the Dutch East India Company about transporting the Bernese Anabaptists to “take these people off our hands, by such means and to such a place we can be confident they will not return,” possibly the East Indies or some remote island. The East India Company did not respond to their request. The authorities then made their own arrangements to transport the Anabaptists to the British colonies in America. In making arrangement for transportation along the Rhine River, they ran into trouble with the Dutch authorities, who protested they would not tolerate religious prisoners being transported through their territory. The Bernese authorities were informed that “as soon as they set foot in our country, they [the Bernese Anabaptist prisoners] would be set free.” That is what actually occurred when, in 1710, these prisoners were on their way to ocean ports for transportation to America. When they arrived in the Netherlands, they were set free.

Another larger-scale forced exile occurred in 1711, which resulted in the scattering of many Bernese Anabaptists along the Rhine River, with the majority arriving in the Netherlands, where they eventually merged with the Mennonite congregations there.

Later, when it became obvious that America offered many opportunities not available in Europe, a large exodus from their ancestral homeland to America took place.

What has come of the Bernese Anabaptists and their descendants in America?

John Gingerich: We see descendants of Bernese Anabaptists in modern-day Amish, Mennonite and Hutterite congregations, as well as many other church affiliations. We see a wide variety of religious practices and beliefs among them, from very conservative to very liberal. In addition to their physical descendants, we also see a spiritual progeny of these faithful forefathers, made up of many people of various backgrounds, races and languages. This, I think, is the most important legacy of the Anabaptists.

As Müller concluded his book, he noted that the Swiss Anabaptists “have become a great people. . . They also contribute to the glory of their homeland, which even now sends them its greetings with the assurance that it has not forgotten them.

“The Lord tills His field. He allows the grain to grow and thrive. In time, the fences that men have erected in the midst of these waving grain fields will no longer be needed.”

Giveaway

I too would be interested in reading this book. Please enter me as well.

Almost forgot; please include my name. Thanks, SRR

Finding your book by "coincidence"

John Gingerich,

In the summer “quilt and furniture Amish auction time” in Wisconsin in 2010, I found a pedler in her tent selling an assortment of goods, some new , some old, but including your book, “Hisotry of the Bernese Anabaptists” for sale for $8.00 which I bought with alacrity.

Today, May 12, 2011 as I was reading Leroy Beachy’s two volume “Unser Leit” I came across the name of the Swiss village of Eggiwil that I have visited and stayed in a B&B in 2002. Sadly, I never went to the “cave church” nearby.

Now after writing nine non-fiction books of my experiences with the AMish, Mennonites, and Hutterites I’m ready to retire and will be able to spend the time to ponder over my reading of Beachy’s two volume living history.

Richard Lee Dawley

Amish Insight

http://www.richarddawley.com

New Berlin, Wisconsin

thank you for this important translation

Mr. Gingerich, I can’t thank you enough for your work translating this important book into English. I have been researching ancestors on both paternal and maternal lines of my family who came from Canton Bern Switzerland and then lived in the Alsace region of France or the Palatinate and all eventually emmigrating to the US or Canada.

Most notably were my 4th great grandparents John Steiner and his wife Elizabeth Stauffer who married in Alsace in 1814. John was a noncombatant in Napoleon’s army who deserted three times, the first two unsuccessfully and the third time successfully. He met up with his young wife, Elizabeth in Switzherland and from there they emigrated to North America, landing in PA, USA and settling in Kitchener, Ontario then later in Ohio. John and Elizabeth’s son, Abraham, lived his life in Ohio, with Abraham’s son, Johnathan eventually moved west to Kansas where or family has lived ever since. I live in the state capital, Topeka.

I decided to research John and Elizabeth before going to see the movie Les Miserables, as I wanted a more personal perspective on those times of strife and rebellion in France. I find John and Elizabeth’s life was likely complicated and full of burdens most of us in America can not likely comprehend.

Your book will likely help me color in many of the details of their life and times and for that, I am most grateful.

Jolene Grabill (original surname in Switzerland was Krahenbuhl)

jgrabill@cox.net

Topeka, Ks.

Bern

Stauffers are from near Thun/Steffisburg and Steiners from the Emmental and Thun too.

Thank You for Your Feedback!

Dear Jolene,

Many Thanks for your kind words. I’m glad you’ve found the book of benefit.

It might interest you to know that I have in my collection a 1737 Anabaptist Testament that belonged to a Christian Kräinbiel (one of the many forms of Graybill/Grabill/Krahenbuhl, etc), who recorded the birth of son, also named Christian in July 1799.

Best Regards,

John Gingerich

Krahenbuhl

Dear Mr Gingerich

I have just stumbled upon your website in my search for the history of the Swiss Anabaptists.

My parents come from a small village in the Netherlands which became the home of about 125 Swiss Anabaptists in 1711, and my mothers family tree is bespeckled with lots of old Swiss names. Her family name is Kraai which may also be from the name Krahenbuhl. Other names in her family tree include Zahler, Stucki and Mayer.

I would love to know where I can buy a copy of your translation, I do speak reasonable German but not well enough to read the original. I now live in the UK so if you have any suggestions how I can buy a copy of your book I would be very grateful.

Many thanks

Annemieke Waite

Where to purchase History of the Bernese Anabaptists

Dear Annemieke, thank you for your interest in the book!

I currently have signed copies listed on Ebay. Just search for “History of the Bernese Anabaptists” and you should be able to find it.

I hope you find the book of benefit!

John Gingerich

Thank you

Thank you John, I have just ordered the book and will let you know how I get on with my research.

Greeting from a wet and windy Bristol!

Annemieke

GIVEAWAY

I would love to win this book also, it sounds very interesting …..

A Memory Renewed

John,

I have two copies of your book, mainly because I was in Eggiwill about 7 years ago that you mention in the book (p. 373, 374, 378) . Also been to Schleitheim in Schauffhausen where the first confession for the Anabaptists was written by Michael Sattler, and his execution site on the Neckar River with an inscription to him chisled in it. Also, Ehrlenbach, birthplace of Jakob Ammann.

Your book was a refreshing reliving of that trip into history, and the groundswell of the society.

Spured by that trip, I’ve written and published a total of eight, non-fiction books about my first-hand experiences with the Amish, Mennonites, ahd Hutterites, and sold 8,500 copies to hopefully, educate a fiction-driven readership.

Thank you for your book.

Richard Lee Dawley

Amish Insight

New Berlin, Wisconsin

A Memory Reviewed

Thank you for your comments, Richard!

The Gingrich Family

My grandfather, Ammon Gingrich, is related to three Gingrich brothers, who came to America from Switzerland in the 1700’s. They settled in the Lebanon County, PA area, which was then Lancaster County.The oldest Gingrich relative is my mother, who is Ammon’s daughter, and is 92 years old. Our family would like to have more information about our relatives. Your book seems to have some answers for us. Is your book available anywhere in PA? Thank you for translation that will help many to find answers. Any other help you could give me would be appreciated. Sincerely, Diane Sattazahn

Lancaster County, PA

PS My mother always admitted to us that she was ‘stubborn.’ 🙂

The Gingerich/Gingrich Family

Hello Diane,

The Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society bookstore should have the book available.

Thanks for Your Message!

John Gingerich

Die Furgge by Katrina Zimmerman

To really understand the Bernese Anabaptists read the book “die Furgge” by Katrina Zimmerman.