Plain Talk About Health: Linguistic Aspects of Mediation Between Amish and Health Care Professionals

The very first issue of the Journal of Plain Anabaptist Communities was published in the Summer of 2020, and in that issue, the lead article was written by Mark Louden, who is the Alfred L. Shoemaker, J. William Frey, and Don Yoder Professor of Germanic Linguistics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

His article focused on what is arguably the most distinctive difference between Plain people and the mainstream of North American society – language. Here are key excerpts from his inaugural article (with some slight editorial changes) in JPAC. – Joe Donnermeyer

Excerpts from Plain Talk About Health: Linguistic Aspects of Mediation Between Amish and Health Care Professionals (by Mark Louden)

Much of the large and growing body of scholarly literature on Amish and Old Order Mennonite health and well-being deals, understandably, with complex biomedical topics (e.g., genetic disorders) as well as practical information for nurses, midwives, physicians, and others who care for Plain patients.

Other researchers have focused on cultural aspects of Plain health. Language matters are discussed only occasionally in works such as these; hence, the motivation for this article, which is based on a presentation I delivered at the June, 2019 Young Center conference (Health & Well-Being in Amish Society).

I draw here on my scholarly background in Pennsylvania Dutch linguistics and practical experience as an interpreter and cultural mediator for Plain people. For several years now, I have been asked to assist in situations in which Plain people interact with outsiders, most frequently in the area of health care.

Plain Bilingualism

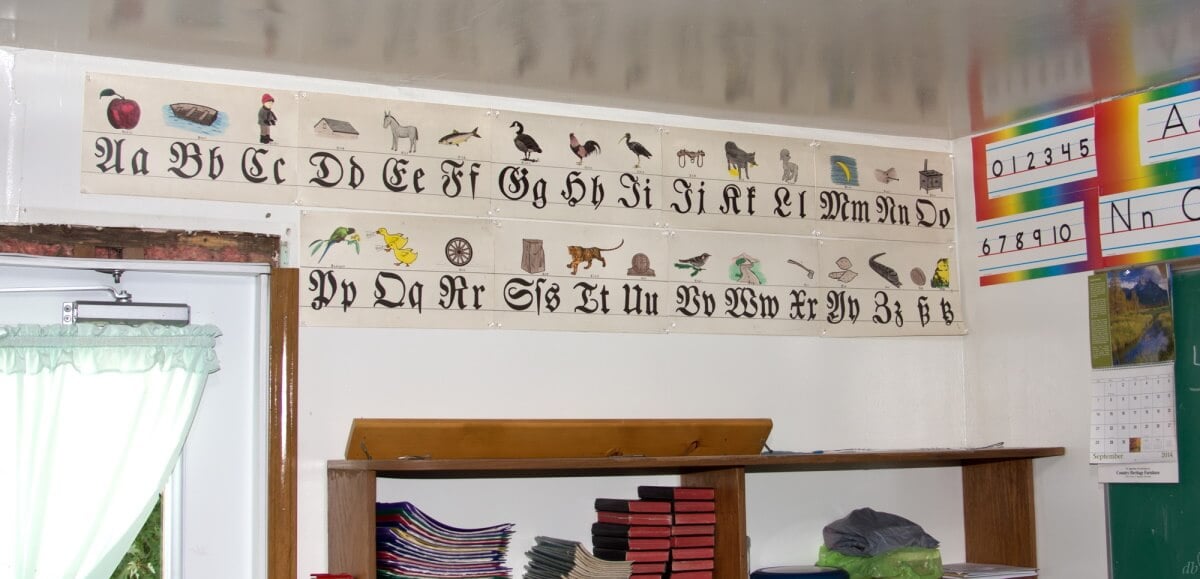

A discussion of any aspect of language use among Plain people will necessarily involve the question of their bilingualism. Preschool-age Plain children typically remain monolingual in Pennsylvania Dutch until they enter school, which for most are Old Order–run schools in which the medium of instruction is English. Smaller numbers of children attend public schools or are homeschooled, but there again, the material is delivered in English.

German is taught as a subject in Plain schools, often on Friday afternoons. The goal of German instruction is to promote basic literacy in the form of the language that is used in worship—that is, the German of Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible and hymn and prayer books.

Immersed in an all-English educational setting, most Plain children become bilingual quite rapidly, such that by the time they leave school after the eighth grade, their oral proficiency in Pennsylvania Dutch and English is more or less equivalent. All languages, especially those used in bilingual communities or in societies with a legacy of immigration, show the effects of contact from other languages, notably in the form of borrowed words.

English, for example, a historically Germanic language, and especially American English, derives about three-quarters of its vocabulary from non-Germanic sources, notably French or Latin (e.g., language, medicine, music) and Greek (e.g., ethnic, telephone, zoo), but also other languages, like Spanish (taco), Italian (balcony), Russian (mammoth), Yiddish (chutzpah), Japanese (tsunami), and even Pennsylvania Dutch (dunk).

Loanwords & Related Vocabulary

Approximately 10–15 percent of Pennsylvania Dutch vocabulary is taken directly from English (loanwords), usually words that refer to objects and concepts that were not familiar to the eighteenth-century founder population. The influence of English on Pennsylvania Dutch extends further, in a less obvious way, on the level of meaning (semantics). Once, when asked why Pennsylvania Dutch is so different from the German spoken in Europe, a native speaker remarked, Fer Deitsch schwetze, musscht du Englisch denke (“To speak Pennsylvania Dutch, you need to think in English”).

The words for body parts and basic bodily functions are typically not borrowed from one language into another. In the Pennsylvania Dutch context, eighteenth-century immigrants did not encounter heads, hands, and feet for the first time after their arrival in North America, nor did they learn to breathe or burp here. Not surprisingly, then, when speaking about basic anatomy and physiology in Pennsylvania Dutch, mostly inherited (native) vocabulary is used, as with en verbroche Bee (a broken leg).

But as medical science has progressed since the colonial era, the English words used in this semantic area are naturally borrowed into Pennsylvania Dutch, for example, hospital. Hospitals in the modern sense did not exist until later, so it makes sense that when they were established in the United States, Pennsylvania Dutch speakers simply called them Hospitals. English-derived loanwords for medical terminology are, not surprisingly, very common in Pennsylvania Dutch. It is notable that in virtually every case, English words like hospital are themselves borrowed, in this case from Latin/French. Other examples of Latinate English words are digestion, monitor, treat. Greek is also the source of much medical terminology in English (e.g., antibiotic, cardiology, thermometer), including by way of French (e.g., clinic).

Aside from loanwords, the semantic influence of English on Pennsylvania Dutch can be seen in three types of vocabulary: loanblends, loanshifts, and loan translations.

Loanblends are compound words that combine native and borrowed elements in translations from one language into another. Examples of these abound in Pennsylvania Dutch, including Emergency-Schtubb and Operating-Schtubb (Schtubb ‘room’).

Loanshifts refer to native words that have had their original meaning adapted to match a similar word in the influencing language, such as the verb doktere (to doctor).

Finally, loan translations are compound words and expressions that are translated verbatim from one language to another, as in the Pennsylvania Dutch word for ‘medicine’, Dokter-Schtofft, which is modeled on the nineteenth-century colloquial American English expression doctor stuff.

Are translation and interpretation necessary?

The intensity of Plain bilingualism and the extent to which English affects the vocabulary of Pennsylvania Dutch raise the question of whether translation (which refers to the production of written texts) and interpretation (oral linguistic mediation) between the two languages is necessary. Strictly speaking, for school-age children and adults they are not; however, there are definite benefits for making language assistance available to Amish and Mennonites when desired, especially in the area of health care.

Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information needed to make appropriate health decisions. Plain people, as members of a distinctive minority population, most with modest incomes and limited formal educational levels, whom some consider medically underserved, are thus on the radar of health care providers located in regions with relatively large numbers of Amish and Mennonites. The fact that they also speak a language other than English, even if they are fluent and completely literate in English, heightens the concern that this may pose an additional challenge to their health literacy.

Pennsylvania Dutch–English interpretation, which involves oral communication in real time, is routine for preschool-age Plain children and is normally conducted by parents; however, under special circumstances, such as forensic interviews, parents and other family members may not be present. But even many Amish and Mennonite adults welcome the opportunity to have interpreters present during serious medical conversations, in the same way that many patients and family members appreciate having multiple “sets of ears” in those settings, both to ensure that they have understood everything a provider has shared and for emotional support.

The comfort offered by the use of Pennsylvania Dutch in medical contexts, especially critical situations, is aptly illustrated by the story of an Amish-born nurse who works in the Emergency Department of Lancaster General Hospital (LGH) and serves as a medical interpreter. His innate cultural competence enables him to provide a higher level of comfort to Amish patients—especially children. The nurse recalls recently helping a young boy from the Amish community whose injuries required him to be transferred to a pediatric hospital. While riding with three medical personnel, the boy remained quiet—that is, until the nurse started speaking to him in Pennsylvania Dutch.

From that moment on, he became animated and talked for the entire ride, telling me about his school and his family. For a small child—especially one who is brought back to the trauma bay, with a group of strangers looming above—just knowing there is someone with you who understands your first language can be very reassuring.

In a manual written for Amish youth that provides answers to important questions about how to live out their faith, 1001 Questions and Answers on the Christian Life, there is a section titled “Our Speech”. One question in this section is “What guidelines does the Bible give us by which to monitor our speech?” The book offers seven recommendations for how Christians should speak, each supported by passages from Scripture. 1. To speak only the truth 2. To be simple and straightforward in our speech 3. To be “slow to speak” 4. To return good for evil 5. Sometimes it is better to be quiet. 6. To be consistent in our speech 7. To be a good witness to non-Christians.

Tendencies of Plain Speakers

The avoidance of speaking about the future with certainty partly explains the caution Plain people feel in discussions of pregnancy and childbirth. In Pennsylvania Dutch, there is a word for “pregnant,” schwanger (identical in German), but the preferred expression is an ekschpeckte sei (to be expecting), which is both a euphemism and a borrowing from English. Even though pregnancy is a frequent phenomenon in Old Order communities, Plain people have inherited a reluctance to speak about the hoped-for outcome of pregnancy, a normal birth. To assume that all will go well for baby and mom would be tantamount to tempting God.

This caution about the future, coupled with the confidence among Amish and Mennonites that God is in control, can lead medical professionals to think that Plain people are “fatalistic,” which can be problematic when a child is a patient. On many occasions, health care providers form the mistaken impression that Plain parents care less about their children’s health than they actually do. The tendency for Plain people to be “slow to speak,” especially in an unfamiliar setting and in English, can reinforce this impression.

In general, Amish and Mennonites prefer to be understated in their behavior and speech. I recall the Amish mother of a hospitalized child telling that child, Du darfscht brutze, awwer du darfscht net greische (You can cry, but you can’t scream). From the mother’s perspective, screaming about pain would do nothing to relieve it, so it was best to avoid what was to Plain thinking an overreaction.

Verbal integrity is a virtue that Plain people aim to embody in their speech, including when accessing health care and they appreciate it when the providers of that care do likewise. Amish and Mennonite patients, like most people, are grateful when providers take the time to listen to patients and their families and explain diagnoses and treatment options in plain language and without rushing. Some providers have remarked that their Plain patients ask more questions than their non-Plain patients, which has in part to do with a general interest in health and well-being and is also connected with their preference for accessing care within the community, thereby avoiding doctors and hospitals as much as possible.

A little Dutch…

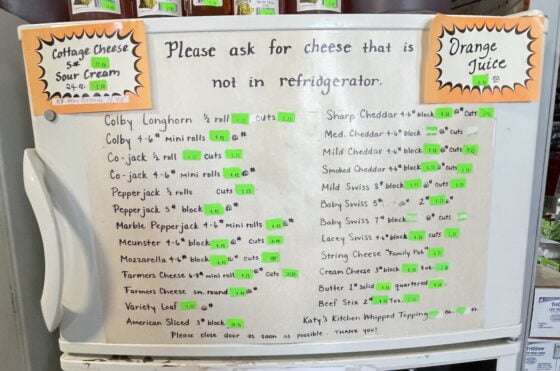

In 2016, an online magazine devoted to science and health featured an article titled “Six Ways to Make a Hospital Better for Amish Patients,” which was based on the experiences of Pomerene Hospital in Holmes County, Ohio, the second largest Amish settlement in the world.

Practical suggestions included hiring a patient advocate who knows Plain culture and Pennsylvania Dutch, providing non-starched head coverings for female patients, being respectful and supportive of the Amish-created B&W/burdock therapy for the treatment of burns, and not assuming that Amish women have no say in the care they receive. But the first suggestion the article offered had to do with language and was titled Bisli Deitsh gayt en langa vayk (“A little Dutch goes a long way”).

Professor Louden is the author of “Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language”, published in 2016 by The Johns Hopkins University Press.

To register for the Journal of Plain Anabaptist Communities, go to https://plainanabaptistjournal.org/index.php/JPAC, and click on register in the upper-right hand corner. Registration requires only a few minutes of your time.

Amish language

I found this article to be extremely interesting! Very informative about the language. And how that may affect healthcare communication.