A Midwife In Amish Country: Your Question Suggestions For Author Kim Osterholzer (Giveaway & Excerpt)

Kim Osterholzer was a midwife apprentice to the Amish in Michigan for nearly a decade. You might remember our recent post on her book A Midwife In Amish Country: Celebrating God’s Gift of Life.

Kim will be giving away a signed copy of her book for a lucky Amish America reader. We’ll also have a Q-and-A post with Kim coming soon.

Kim will be giving away a signed copy of her book for a lucky Amish America reader. We’ll also have a Q-and-A post with Kim coming soon.

Enter to win a copy of A Midwife in Amish Country

But first, we want to know if you have any questions for Kim about her experience with the Amish. Feel free to leave them on this post.

Adding a question here will enter you in the giveaway. I’ll choose the best ones to pass on to Kim for the Q-and-A post.

A Midwife In Amish Country: Celebrating God’s Gift of Life – An Excerpt

We’ve also got another excerpt from A Midwife in Amish Country.

In this excerpt from Chapter 2, Kim describes how her expectations of Amish life collided with reality.

—

Chapter 2

One of the first births I attended through my apprenticeship was for an Amish family living at the extreme northern edge of Indiana in late September, 1993. Jean called me an hour or so before dawn and sent me scampering into the day with my hair flying and my heart pounding.

The mother-to-be, Salome Hochstetler, was an angelic creature, if there ever was one–tiny and graceful as they come. She suffered a disorder of some sort. I failed to retain its name, but remembered it affected the composition of her musculature and left her limping. She’d also endured the loss of a child a few years earlier, though what happened was never explained to me, and I felt I shouldn’t ask.

I thought of her pain and sorrows every time I saw her, ever reminded by her awkward gait, and I was struck by the way she refused to allow her trials to dampen her spirits or dim her faith.

She greeted us at her door, smiling and laughing as she always did, and we knew we’d arrived too early, so we passed the morning checking on a number of families in the area while we waited for Salome’s labor to get more serious.

Things picked up gradually toward noon, but still only very gradually. Jean suggested we go for a ride in her car in hopes the bumps and jostles would strengthen her pains. The trip accomplished what we hoped but, by the time it did, Jean realized she’d lost her way in the labyrinth of rutted, back-woods roads. Salome, in spite of contractions washing one after the other over her diminutive frame with increasing intensity, gamely straightened in her seat, laughed her good-natured laugh, and guided us back to her home as she ran her hands round and round her swollen, surging belly.

My heart sank a mite as we pulled into her driveway. For as much as I enjoyed Salome and her husband, Nathan, I struggled mightily to bear their home. The young couple lived in a barn of sorts, a barn that doubled as one edge of a full to overflowing pigpen. Salome’s living arrangements shocked me to silence at my first visit with her and that shock spilled over to vex my entire first year attending births.

—

When I began attending home visits with Jean, the disparity between my expectations of the Plain People and the actual condition of their lives proved a deterrent. Where I’d pictured the prim, pristine houses of Amish film and fiction, I found bluntly functional homes filled with a bustling, Spartan folk wearing patched and sweat-stained clothes. I was taken aback by the rough hands, the weather-battered faces, the round and weary shoulders, the bare and blackened feet, the grossly swollen ankles, and the legs strangled with bulging veins.

I blanched at the number of younger families living in barns, in sheds, and in the basements of partially-constructed homes. I reeled at the harsh realities of houses warmed only by wood or coal stoves and lit only by lanterns, serviced by pumps at kitchen sinks, by windmills that failed to draw water on still days, by tiny propane-fueled refrigerators and wringer washers, by wash boards, by yards and yards of clotheslines, by sad irons and push-reel lawn mowers, by chamber pots stashed in wooden boxes, and by dark, drafty, stinking outhouses.

I had to learn to regard with nonchalance the rolls of fly paper that dangled from the ceilings and snagged my braids when I leaned too close, the mice scampering under doors and along the edges of baseboards, the bicycle wheel drying racks suspended over stoves and trimmed with perfect circles of damp socks or beef jerky, the ropes strung with chicken feet and stretched between outbuildings, the carcasses of unrecognizable animals littered about the yards by naughty dogs, the boxes of chirping chicks or orphaned lambs in living rooms, the riotous pigsties, the milk cows loose along roadsides, and the giant draft horse we once found tied to a basement support pole to warm up after he’d crashed through a frozen pond.

I was forced to listen unperturbed and respectfully to the abundance of old wives’ tales such as, if you reach your arms over your head to hang clothes on the line or to wash windows in the last trimester of pregnancy, your baby will turn breech; if you get a scare anytime at all while pregnant, your baby will be born with a birth mark; or if your baby isn’t fed a sip of cold water soon after birth, it will tend toward belly ache.

I had to appear unfazed by the severity of their religion, a religion promising no guarantees in return for the strictest adherence to the sternest rules. No electricity, no telephones, no vehicles. Nothing to ease the rigors of life. Life is fraught with endless work and limitless opportunities to flounder and fail.

In the beginning, all of that so clogged my senses I could hardly see or hear the people I was called on to serve, and I began to suspect I wasn’t made of the stuff of midwives after all.

You can read the first excerpt we posted from Chapter 1 here, or get A Midwife in Amish Country in hardcover or Kindle version here.

How does your experience with the Amish compare to the PBS program, "Call the Midwife"?

Kim, I’m a big fan of the British program, “Call the Midwife”, broadcast in the USA on PBS. I’ve also read the three books that inspired the series.

Are you familiar with this program? How do your experiences with the Amish compare with midwifery in the dock neighborhoods of London in the 1950-60 era? Both types of homes lack many of the modern conveniences.

Thanks!

Attending

Do Neighbouring women also attend the birth with assisitance to you

Hospital

Do you ever have a high risk patient that you need to refer to a specialist? Have you ever had to send a woman to the hospital because there could be problems with the birth?

questions

What is the backup plan should the birth process get complicated unexpectedly?

How are arrangements made to insure that emergencies can be handled efficiently?

What type of education process occurs for the Amish couple before birth about the process?

Does the father or other family members attend?

Intersting

I read a few short sentences and was very interested to learn that Amish families struggle also. I don’t want to read further because I want to read the book. My question is, is it pretty common for their to be such struggles and how can they afford to pay you with no insurance. My apologies typing this on my phone 🙁

Hi Kim

I was wondering if any young unmarried women out of wedlock have children? I know sometimes they are shunned, but are some forgiven and have their child in the parents home ?

Thank you

Question

Hello, I love and appreciate the way that the Amish have chosen to live their lives but I do have a question, when everything goes wrong in your life, nothing seems to go right and it never changes, how do you deal with that? How do you attempt to turn your situation around? I’m hoping im not being to forward with my question and I thank you for answering.

Celebrations for the Baby

Does the Amish have any celebrations for the baby before/after it arrives?

Getting to know you

I remember when I was pregnant I wanted 5o know the doctor who would be delivering my baby. It made me trust him and made me feel safer for me and for my growing baby. Do you try to know the women you deliver? Do they ask for visits before the birth? If you do, I can only imagine the friendships you must gain both before and after the delivery.

Emergencies

I had a uterine atony after giving birth to my first child, but as I was at a hospital, I was able to get immediate care, including a blood transfusion. I was wondering if you have ever seen this kind of complication and what you did. Were you able to transfer to a hospital or were you able to treat it at home?

Thanks for having this Q&A, its really interesting to get a glimpse into Amish life.

A Midwife In Amish Country: A question for Author Kim Osterholzer

What has been the hardest delivery for you and what made you

want to become a Midwife for the Amish?

Thank you

Other Amish Communities

Have you visited other Amish communities, and did you find them as poor as the one that you described in this passage?

Do you lose many babies? If so how do they deal with it?

Are you ever too late?? and the baby has already come??? I am a volunteer emergency medical responder and i know that one lady had already had her baby….i have never been more scared in my life lol…But considering i have not had kids of my own i had no idea what to expect lol…

Curious

When you were a young girl did you think that you were going to be a midwife and How do you learn about midwifery.

Who is at the birth

Are family members present at the birth?

Apprenticeship

From the short intro, it seems like your apprenticeship was 10 years. If I am reading this accurately, why was it so long? And what was your background prior to this? Or did you go straight into midwifery?

I look forward to reading this book.

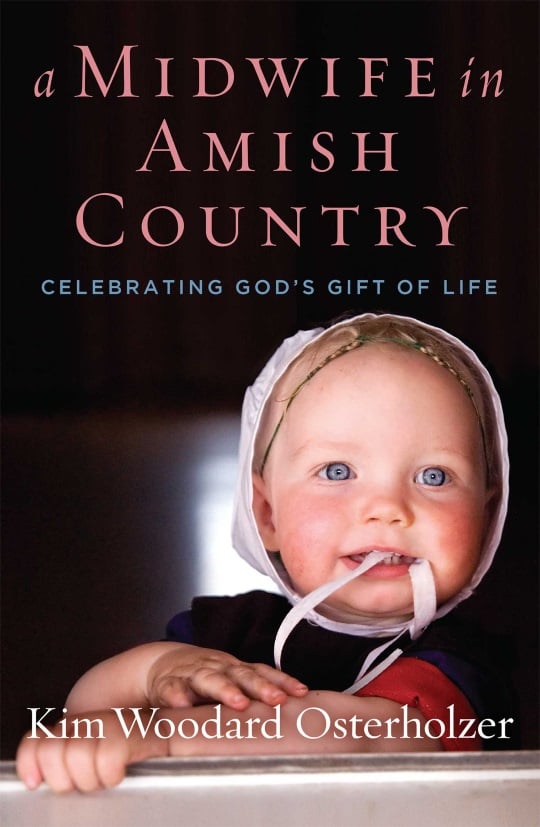

Book Cover

This is probably as lovely of a book cover that I’ve ever seen. My question is:

Is the baby on the cover a true amish little girl?

Your Patients

I was wondering if the majority of your patients were Schwartzentruber Amish, since the way you described their living conditions sounds so extremely plain. Thank you!

Amish Midwife or midwife to the Amish?

I have had the honor of attending about 15 home births as a support person for the laboring mother. Two of my children were born at home with a lay midwife. My niece is a registered midwife,just starting her career at a birthing center and expecting her first child next month. So I do understand the kind of service and commitment this kind of work does require. I am wondering if you are Amish and if not, is it possible for an Amish woman to be a midwife and thus, to be available for this kind of service to others?

I look forward to reading your book. Thank you,

What kind

I noticed you mentioned the lady calling you and the two of you taking a ride in a car. Just wondering what branch of the Amish was she? We have a small community of Amish near us and all I see are big houses and barns. It’s hard to imagine people living like that, but I’m sure they do the best they can with what they have. I agree about the cover, and I can’t wait to read the book.

Attributes in midwifery

What attributes do you think make for a great midwife? Was there ever a time you thought, “nevermind, this isn’t for me”?

Question

It sounded in the early part of this blog that you trained as a midwife and were with the Amish for a decade. Do you still work as a midwife, and, if so, do you serve the Amish community or the non-Amish community? Do the midwives provide follow-up care for the babies or just work with the mothers and babies until the babies are born? Your book sounds fascinating!

Training & Calling

When and how were you called to become a midwife?

A Midwife In Amish Country: Celebrating God’s Gift of Life

I have been fascinated with Amish life. How soon during a pregnancy does a woman know she is having trouble, and is she allowed to go to a hospital from then until birth?

Breech Presentation

Have ou had to manually turn a breech around? If so, did you do it externally? How difficult is it to get enough water to wash the newborn with?

Ethics

My question:

Did you ever, as a midwife, find yourself in a situation where you had to review or even change your ethics regarding pregnancy/birth/postpartum?

Best regards,

Anna

Fun Memory

What are some of your funniest moments while being a midwife?

A Midwife In Amish Country

Reading the chapter from your book was a real eye opener. After reading Amish fiction and seeing all the neat farms on Keeping up with the Amish, these people really need Jesus in their lives.

You DO know that Amish fiction and TV is full of misinformation, right? Have you ever had a conversation WITH an Amish person? I have an Amish neighbor/ friend who I have often heard say, “Without the blood of Christ, everything else is pointless.”

Question: If you were to...

…if you were to encounter Mrs Eicher, or Mrs Schwartz — the two Indiana Amishwomen who recently have been in trouble for practising midwifery — say, in the aisles at the Geneva, IN, Wal-Mart — what would you say to them? If you were to reach out to them, as colleague to colleague, what would you say to them?

When did Geneva Indiana get a Wal Mart.

What preparations would a typical Amish woman make in her home for a home birth?

What made you decide to become a midwife? Do you enjoy being a midwife?

I Feel Sad . . .

after reading the excerpt of your story. We’re headed off to Holmes County for our first visit and well, you can imagine after years of reading Amish fiction, I’m not imagining them living like you wrote. Reality check. Thanks. What is your biggest blessing of having worked with the Amish for so long, so hard?

Amish standards of living vary widely

I’ll just jump in to say that there is a lot of variety in the material conditions seen in different Amish communities.

In the plainer and less prosperous communities you are more likely to encounter what Kim describes. You see Amish living in shop homes and without a lot of the trappings that you might find in a less plain community.

There are also many Amish who live in traditional homes which have many creature comforts and in many ways resemble non-Amish homes. Have a look at the photos on these posts for examples: https://amishamerica.com/look-inside-an-ohio-amish-home/

https://amishamerica.com/look-inside-a-new-york-amish-farmhouse-9-photos/

And here’s one on the plainer side: https://amishamerica.com/look-inside-swartzentruber-amish-home/

In Holmes County, likely the most diverse Amish community in terms of different Amish groups, you’ll find the very plainest Amish which may even live more plainly than what Kim describes here, and some Amish which you might consider quite “fancy”, and everything in between.

Well, THAT chapter does not describe life in our community. Not one of our relatives or friends or neighbors lives like that! I’d be pretty horrified to step into a situation like she describes. But does it exist? Sure does! But I will say the same thing over and over — not all communities or groups are the same! And i am thankful for that.

I’ll go home thankful for our bathrooms and battery lamps and good health and the common sense to ignore superstition for education and grateful that Jesus Christ is my Savior.

I’m ready to start reading the book… in my recliner in our clean living room. 😉 You know how to catch a reader’s interest Kim!

Still a midwife?

I would guess by reading all of the above that you are no longer acting as an apprentice midwife. Is there a reason why you quit? I also love the cover of your book and am very anxious to read it.

I’ve read the excerpt and want more! What happens next?!

Amish Midwife

How old was the youngest patient you had to deliver a baby for?

Were there complications with that case?

Would love to win book. So enjoy reading about the Amish.

twins and triplets

How do you handle twins and more , What was your reaction when you knew when the mother was only carrying one and two or three babies came?

A Midwife In Amish Country: Your Questions Suggestions For Author Kim Osterhholzer (Giveway & Excerpt)

What was the oldest woman that you helped give birth?

Living with the pig sty so close makes me wonder about the stench and sanitary conditions. Are infections a problem in these situations?

Moment

Did you ever have one moment where you rethought what you were doing, and considered leaving being a midwife for the Amish?

If so, what was that moment?

Thank you 🙂

Do you treat others besides the Amish?

Blessings

Blessings to you for all the beautiful babies you have delivered. God bless you!❤️

Blessings

Blessings to you for all the beautiful babies you have delivered. Would love to read your book.

Blessings

Blessings to you for all the beautiful babies you have delivered.

Braids on cover

What is the significance of the braids on the baby on the cover? I haven’t seen that before. Is that a common Amish baby hairstyle?

Family planning

Is family planning allowed in the Amish communities where you work? Do you advise on that? Have you seen woman whose health was harmed by having too many children?

Helping also for the Amish Community

I would love to help in the Amish Community, How can I help deliver babies. I am only a Medical Missionary and only do natural remedies that God has made from the ground. Can you use my gift that God has given me? If so please email me.

Respectfully

A Watchwoman on the Wall

Australian Amish Afficinado

Do you need to be a Registered Nurse or equivalent to be a midwife?

Question

Are any Amish children ever allowed to witness the birth of a sibling? I don’t mean very young children, but those old enough to understand.