Cathedrals, Castles & Caves: Winner & Excerpt (“Preacher On The Run”)

We have a winner today of Marcus Yoder’s new book, Cathedrals, Castles, and Caves: The Origins of the Anabaptist Faith. If you missed it, you can find the Q-and-A with Marcus here.

Excerpt from Cathedrals, Castles, and Caves

But before we get to the winner, an excerpt from the book. The following is the full Chapter 24, entitled “Preacher On The Run”.

But before we get to the winner, an excerpt from the book. The following is the full Chapter 24, entitled “Preacher On The Run”.

In this excerpt, we learn about early influential Anabaptist Menno Simons, and one lesser-known martyr, Sicke Freerks, a catalyst of sorts for Menno’s movement towards Anabaptism. In Menno’s story, you will also see reference to the “perverted sect of Münster”, meaning a radical Anabaptist group which controlled the city using violence and other abuses in the years 1534-1535 (and which is detailed in the preceding chapter in the book).

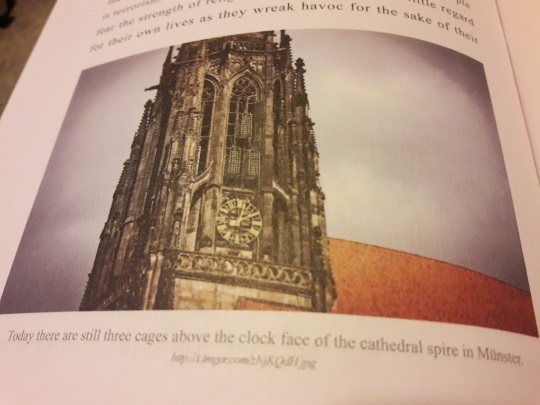

On our original Q-and-A post, commenter Jon referenced the cages holding the executed bodies of three sect leaders, which were hung from a church spire in Münster. Three cages (though not the original ones) still hang there today, which you can see in this photo from the book:

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

PREACHER ON THE RUN

To understand the life of Menno Simons, we must first meet a man named Sicke Freerks who, in 1531, was martyred for his faith. Freerks, a tailor, had been baptized and then publicly executed for that baptism in the city of Leeuwarden, in the Netherlands. A young Catholic priest serving in the small, nearby village of Pingjum heard about the death. Menno Simons was appalled that such a good and pious man would be killed for an act such as rebaptism. Why was someone this good condemned to a cruel death, and even more thought-provoking, why was Freerks willing to die for his faith?

Menno Simons had been dedicated to the church at a young age by his peasant family. Trained in the life of the church and in theology, which entailed learning Latin and Greek, Menno was ordained a priest in 1524. He served twelve years as a priest in Pingjum and then in his home village of Witmarsum until a crisis of faith moved him to resign and leave the Catholic Church in 1536. Like many village priests, Menno’s life was ordered by the Church and its system. He seems to have spent little time in study and confessed that he most often joined his fellow priests in “playing cards, drinking and frivolities of all sorts, as was the custom of such unfruitful men.”(1)

It was not until his own doubts and questions became strong enough that Menno turned to the Scriptures for answers. It was some two years into his service as a priest that Menno began to search the Scriptures in his struggle for answers. He had, in fact, feared the Scriptures and once said that he had never opened them until his doubts became overwhelming.

As Menno began to read and study the Bible, he discovered that it did speak to his doubts. In that process, he began to doubt the Church and its teachings. By 1531 when Freerks was executed, Menno was traveling a path away from the established teachings of the Catholic Church. Yet it would take considerable time and the debacle at Münster, which Menno referred to repeatedly as the “perverted sect of Münster,” to move Menno to his own rebaptism. It is likely that some of Menno’s parishioners, including his brother, were swept into the fanatical ideas of that movement. Menno attacked the Münsterites publicly and became known as a strident voice against their abuses, yet it only deepened his own angst and the turmoil in his soul.

As the siege tightened around the followers of “King Jan,” those who wished to join them were held up in the surrounding areas. About three hundred souls, including Menno’s brother, had entrenched in an old monastery. They were quickly seized, and all were either slain in the skirmish or executed afterwards. This event left a lasting impression on the searching priest. While he understood and declared that they had a false faith, their willingness to die, even in error, spoke to his soul.

Menno wrestled deeply with the fact that in his own search he had found some measure of truth, but was unwilling to declare his own findings openly. If he would have done so, he believed, he could have given those three hundred people the shepherding necessary to keep them from the error of their way and perhaps avoid the needless bloodshed. Menno later wrote, “The blood of these people became such a burden to me that I could not endure it nor find rest in my soul.”(2) In that anguish, Menno Simons realized that he too, like Sicke Freerks, must make Christ central to his life.

Eventually, the anguished Menno chose to give up the priesthood and join the Anabaptists. He was re-baptized by Obbe Philips in 1536, and by 1537, had assumed some spiritual leadership as a pastor and teacher. Menno’s deepest concern was to articulate the differences between the way of Christ and the error of the Münsterites. Even before his adult baptism, he wrote a broadsheet against the “Great and Fearful Blasphemy of John of Leiden” (1535).(3) The title page of the booklet included I Cor. 3:11, as would the rest of Menno’s writing: “For other foundation can no man lay than that is laid, which is Jesus Christ.” It was on this foundation that Menno chose to build, and it became the theme of his life and ministry.

Menno married sometime prior to 1541, and he and his wife — whose name is lost int he fog of history — had at least three children. Menno died in 1561, only twenty-five years after his baptism, preceded in death by his wife and two of the three children. His life was one of hardship, pain, and always moving from one area to another. In accepting this call, Menno knew that he was putting not only himself, but also his wife and children, at risk of persecution and death.

In committing to follow Christ first and then to lead the church, Menno became a fugitive for the rest of his life. He was considered so dangerous that not only was a bounty offered for his arrest, but it was illegal to give him or his family shelter and aid. If someone was caught aiding him in any form, the punishment was death! Despite this kind of pressure, Menno lived to be an elderly man and died of natural causes. His recognized leadership also led the authorities to name the Anabaptists, “Mennonists,” and then later, Mennonites. The Anabaptists themselves preferred to be called Taufer (baptizers) in German and Doopsgezinde (Baptists) in Dutch.

Menno was able to concisely articulate theology and by all accounts preached well and wrote better than the common man. His influence was not necessarily in being a great theologian, a powerful preacher, or even an eloquent writer. Rather, his greatness lay in his ability to engage the vital message of the day and steer the new movement away from the violence of Münster. His deep convictions, expressed in his view that authentic Christianity was about discipleship, were developed in the cauldron of deep anguish and pain as he wrestled with his own faith. He built no masterful theology but called for a life of holiness and gelassenheit. His vision of a church built on Christ, and a separate kingdom that would not fight or resort to violence, stabilized a movement rocked by the mess of Münster.

Even today, Anabaptists do not consider Menno Simons to be a founder or prophet, but recognize that he had a profound influence on our story. He was a gifted speaker, a prolific writer, and had the ability to unite the small and widely scattered groups that made up the Anabaptist movement in Holland and Germany. His writings have been printed in multiple languages and are still in use in Anabaptist circles today.

The authorities considered Anabaptism to be dangerous to not only the spiritual welfare of their realm but also the social and political structure of Europe. Anabaptists taught that the decision to follow Christ and the church should not be connected in any way to the political system. Christ’s call to discipleship was open to all adults who would answer, rather than dictated by politically appointed preachers or a distant pope. Menno helped the Anabaptists return to this core teaching after an element of Anabaptists had physically taken over the city of Münster.

We must also consider the life of Sicke Freerks who died for his faith. In his death, he was instrumental in forcing Menno to examine his own life. He could not know as he suffered and died that God was using his witness to change a young, alcoholic priest who would profoundly shape our lives even today. In the same way, none of us know how our lives will influence future generations. So we must live and die with the same commitment to following Christ that Sicke and Menno demonstrated as they lived and died nearly five hundred years ago.

(1) J.C. Wenger, ed. The Complete Writings of Menno Simons (Scottsdale, PA: Herald Press, 1984) 5.

(2) Wenger, 12.

(3) Menno Simons The Complete Writings of Menno Simons edited by J.C. Wenger (Scottsdale PA: Herald Press, 1984) 32-5.

Cathedrals, Castles and Caves Winner

I drew a winner at random from your comments using random.org. The lucky winner is comment #12, Tim! Congrats, Tim. Send me a shipping address for your book (ewesner(at)gmail(dot)com).

Get the Book

If you didn’t win, you can pick up Cathedrals, Castles and Caves at JPV Press. Thanks to Marcus and to everyone who commented and share their thoughts.

Congratulations!

Congratulations Tim! Enjoy the book!

The excerpt was a great read, and looking forward to my purchase!

Thank you Gayle! I look forward to reading it and adding it to my library.

This is my desire.

We must also consider the life of Sicke Freerks who died for his faith. In his death, he was instrumental in forcing Menno to examine his own life. He could not know as he suffered and died that God was using his witness to change a young, alcoholic priest who would profoundly shape our lives even today. In the same way, none of us know how our lives will influence future generations. So we must live and die with the same commitment to following Christ that Sicke and Menno demonstrated as they lived and died nearly five hundred years ago.

Brethren

My question is for anyone who has read the book.

Does the author mention the Brethrens at all?

Following Christ

Many Christians desire to follow Christ which is always an example in some way. When God touches your heart and causes you to realize that Jesus is the center of all life, there often needs change of actions and thoughts to occur. What does following Christ mean? Many different things but mostly that he is Lord and savior. Lord over everything including your life. Savior, because you realize that you never follow him perfectly and that requires saving from disobedience. So as you go through life, you live in the faith of Jesus being Lord over all and savior when you disobey and repent. No greater joy is possible with that truth that God put in your heart. You live anew! That is worth following.