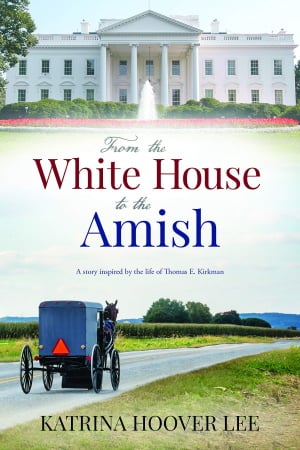

From the White House to the Amish Excerpt & Giveaway Winner

Today we’ve got a winner of Katrina Hoover Lee’s From the White House to the Amish. But first, Katrina has kindly shared an excerpt from the book – the Prologue and first two chapters. I hope you enjoy these as much as I did. You’ll find the winner and purchase links at the end.

Today we’ve got a winner of Katrina Hoover Lee’s From the White House to the Amish. But first, Katrina has kindly shared an excerpt from the book – the Prologue and first two chapters. I hope you enjoy these as much as I did. You’ll find the winner and purchase links at the end.

Prologue

Tom and Sharon left Washington, D.C., on a warm spring morning when the cherry trees were in full bloom. The birds and the buses woke up together, chirping and honking, each in their own language. Tom opened the back door of the pale green Renault and threw in their luggage. The little Renault was a good car for getting around the city; he hoped it had the stamina to make it all the way back to Indiana. Sharon and Jeff soon fell asleep, and Tom was left with his thoughts.

Did I really work beside President Eisenhower? he asked himself. If someone had told him that he would someday do sketches for President Eisenhower in a small room of the White House, he would not have believed it for a minute. If he had been told that the President would at times burst into the room and talk to him as he painted, it would have seemed an idle tale, like a strange dream. But now, Tom’s life seemed more like a nightmare, and working in the White House was a reality that had passed.

Tom turned onto the Route 1 bridge. He could not see the White House, but he knew it was there to the north of the Washington Monument. The White House calligraphy team would be designing nametags, menus, and invitations—without him. Although President Eisenhower was feeling much better after his illness, he and Mamie still avoided stacking the calendar too full of social events. Now that Eisenhower’s second inauguration was over, the calligraphy department was slow.

Once across the Potomac River, Tom did not look back. He pulled onto Route 50 and headed for the topsy-turvy West Virginia hills. At least this trip was better than the last trip he had taken from Washington, D.C., to Indiana.

Tom’s mental state was calmer than it had been on that other trip. Gone was the adrenaline and the shock. Gone was the desperate tension of hoping his mother would recover. He no longer hoped, no longer prayed, no longer made bargains with God. The bargains were over and done. God had not heard, had not cared, had not moved on the behalf of Tom Kirkman. And now God could not expect Tom to move on His behalf either. Perhaps there was a God who had created the world. Tom wasn’t sure. But was there a God who did great things?

No.

chapter one

The Chicken House

Tommy Kirkman entered the world in 1934, at a time when the country exhaled misery and gloom. The shops and streets in southern Indiana echoed not with coins falling into cash registers, but with dark gossip. Several years later, as Tommy toddled after his father into the local hardware store in Bedford, he could hear the anxiety in the voices of the adults. But their words meant little to him.

“Have you seen that hotel in Vincennes, Doc?” the hardware store owner asked Tommy’s dad. “Great big building, six or eight stories high. Started building it before the crash, and then . . .”

The man slapped his hand onto the counter of the hardware store, making the screws in Dad’s purchase bounce and roll. Dad’s real name was Roscoe, but his friends called him Doc. Dad was a powerful skyscraper of a man with a deep, firm voice. His dark wavy hair was piled on top of his head like a dome of black wire. When he smiled, which was not often, he liked to keep his mouth closed to hide two crooked teeth.

“Yes, I drove past a few months ago,” Dad said. “It’s a shame. Think of all the money that went into those steel beams. It’s all just going to waste.”

“Whole country is crumbling,” the hardware store owner mumbled. “Everything okay with you, Doc?”

“Yes, we are fine. Don’t have a lot, but we are fine,” Dad said.

Tommy didn’t care about Wall Street or foreclosures or President Hoover or President Roosevelt. He didn’t care about the depressing black and white photos in the newspaper or the bleak headlines. He felt no distress about the lines of grown men standing outside soup kitchens. The mysterious word Depression did not trouble him.

Tommy was fine because every morning he awoke to his mother’s soprano voice singing, “Praise the Lord, Praise the Lord!” or some other cheerful melody. He smelled cooking oatmeal or sizzling pancakes and heard the clatter of bowls and spoons. Coffee always brewed in the kitchen. It was the Kirkman curse, according to Dad, who drank it in large quantities.

Tommy was fine because Grandpa and Grandma Franklin had given them a dog recently. Tony was a black and white shepherd pup with soft fur and, surprisingly, one brown eye and one blue eye. Tony and Tommy understood each other and were best friends, even though one of them was not allowed to live inside the house.

Tommy was fine because he could draw pictures. Sometimes he drew on scrap paper. Sometimes he drew in the sandy soil outside the house—as long as his little one-year-old brother Joe stayed out of the way. Sometimes his older sisters Patsy or Carol let him use their Crayolas to draw on a piece of notebook paper.

Tommy was fine because on Sundays the Kirkmans attended Avoca Baptist Church. They listened to God’s Word and sang. While some churchgoers barely mouthed the words of the Gospel songs, the Kirkmans sang without inhibition. On the rare occasions they were absent, the church’s singing suffered. On Sunday afternoons, the family played games, read books, drew pictures, and sang. Often Tommy’s older brothers Bob and Bill turned on the cabinet radio, and together they listened to music and voices from faraway places like Chicago or Washington, D.C.

Tommy was fine because in the evenings, when the cow had been milked and the light grew dim, the family sat peacefully around the living room. He loved to watch his mother crocheting in her rocking chair, her silver hook flashing like electricity in and out of the bright strands of yarn. Above the yarn, her bright, intelligent eyes darted from her needle to the family sprawled around the room. Her quick smile revealed perfectly straight teeth. He loved watching his father, uneducated but intelligent, reading the newspaper. Sometimes Dad whittled away at wood projects or mended a broken household tool. Every now and then when a song came over the radio, Dad got to his feet and held out his hand to Mom. Laughing, she put her hand in Dad’s and they twirled around the room until the song was finished.

Every night ended the same way—with the whole family singing together. Then, before Tommy fell asleep, he would hear his father say “good night” and see his mother’s beautiful smile.

But then in 1938, suddenly Mom stopped singing, and Tommy was not fine.

It happened when Dad came in with the announcement that he had lost his construction job. He then tried to get odd jobs, but no one had enough money to hire him. With no income, the family fell behind on the mortgage, and the bank foreclosed on their house. Tommy’s parents were $500 short. But with no money to spare, it might as well have been a million dollars.

One evening when a sloppy spring rain was turning everything to mud, Dad came in the front door. He took off his muddy boots and went to the kitchen where Mom was making supper. Tommy, four years old, trailed after him, arriving just in time to see Mom’s hand frozen in mid-air, holding a spoon.

“A chicken house?” he heard Mom ask, her face as pale as milk in a bucket. “To live in?”

“Not for long, Bernice,” Dad said. “Just until we find something better.”

Tommy could not see his father’s face, but his voice sounded tired and gray. Tommy knew his dad and mom did everything together. They sang together. They prayed together. They planned together. They loved, taught, and disciplined their children together. Now, they suffered together.

That night, Mom didn’t sing.

“Thank God it is almost summertime,” she kept saying over and over again as the family sat down together. “If you think that’s best, Roscoe, that’s where we will go for now. Do you think it’s dry?”

“If it isn’t, we will make it dry,” Dad said. Everyone felt better instantly. Since Dad could fix anything, it would be the easiest thing in the world for him to fix a leaky roof.

The next day they all walked down the road to look at their new home.

The neighbors’ chicken house was a wooden rectangular building. On one side of the house, the wooden shingle roof was so high that a person couldn’t touch it even by reaching up, while the other side was low enough for adults to bump their heads on it.

Near the corner on the high side of the chicken house was a door. It was made of planks, held together with a Z-shaped brace. Two windows let light in beside the door. They were covered with oiled paper, so you couldn’t see through them.

Tommy thought it was going to be a great adventure to live in a chicken house. He scraped old chicken droppings off the floor and spread clean straw for a bed for himself and baby Joe. Dad tied a string from wall to wall and hung up an old sheet to divide the chicken house into two rooms, one for sleeping and one for eating.

“Oh, dear Lord,” Tommy heard Mom say as she swept the floor. “If only we had a new broom!”

Tommy had never noticed his mother’s broom, but he looked at it now. It was worn down to the wire that held the broom bristles together. Here on the rough chicken house floor, the broom was almost useless.

Tommy was still staring at the broom when Mom looked up and caught his eye. She smiled a tired smile.

“It’s okay, Tommy,” she said. “A broom is just a little thing. But still, we can pray about little things. God hears big prayers and little prayers.”

A few hours later, as the family continued setting up house, Jimmy, the Fuller Brush salesman, arrived in his peddler’s truck. Fuller Brush was a company that sold all kinds of brooms and brushes. They offered brushes for horses and hairbrushes for humans and cleaning supplies of every kind. On the outside of the truck, bright new brooms waved their bristles toward the sky.

Jimmy knew everyone in the area—and he also knew how the Great Depression was affecting each one. He knew that Doc Kirkman had no money to buy his brushes or cleaning supplies. Still, he stopped to check on them. Everyone liked to talk to him as a way of staying in touch with the community. Today, Jimmy didn’t have much to say when he heard that the family was moving into a small chicken house.

“Can we get a broom?” Tommy whispered to his mother.

“Shhhh,” Mom said. “We don’t have money for a new broom. That’s why I prayed about it. If God wants us to have a new broom, He will provide one.”

Jimmy chatted with Doc Kirkman for a few minutes, wished everyone the best, and drove away with all his lovely brooms and bristles waving back at Tommy from his truck.

After the chicken house had been cleaned as well as possible, Tommy’s older brothers Bob and Bill brought in the kitchen table and the chairs, as well as Mom’s rocking chair and the cabinet radio. They also carried in the family’s two bed frames and mattresses. Tommy’s older sisters Patsy and Carol made the beds. For the boys, they laid blankets on the straw on the floor. Tony, the black and white puppy, raced around, darting between everyone’s feet and making everyone both frustrated and more cheerful all at once.

When the kitchen table had been set up in the middle of the front partition of the chicken house, Mom set a white doily on it. “Carol, run to the woods and pick an armful of trilliums,” she said. “Just because we live in a chicken house doesn’t mean we aren’t going to decorate.”

Mom cleaned the straw and dirt out of some chicken nest boxes that were nailed to the wall. Each big wooden box was divided into four rows of smaller boxes with holes about a foot square. Mom said the chickens went into the little boxes and laid their eggs there.

For now, Mom used the cleaned boxes to store her dishes. The dinner plates went into one nest box and the tin cups into another. She then carefully put her glass pitcher into another one, and the crock of coffee and the coffee pot went into still another.

A few days later, Tommy awakened early. Unwrapping himself from his blankets, he heard Carol go outside to get water from the pump. She had barely left the chicken house, however, when she burst back in.

“Mom! Mom!”

“Carol!” Mom said. “Not so loud! You’ll wake up all the others. The sun is barely up.”

Tommy scrambled out of his bed on the floor and peeked around the curtain to see what was going on.

“But Mom,” Carol went on, “there’s a broom lying outside!”

There was a moment of silence as Mom looked up from the eggs she was cracking. She eyed Carol over the top of her glasses.

Then, without a word, she set down the bowl of eggs and followed Carol outside. There, lying in the grass close to the road, was a brand-new broom. “Well,” was all Mom said.

Tommy and Joe had followed Mom out of the house. Even Dad, who had been washing at the pump, came over to see the broom.

“Perhaps God sent this broom for us,” Mom said. “But it could be that it fell from Jimmy’s truck. Remember how he sets them into slots on the sidesof his wagon?”

“But Mom!” Carol said. “Can’t we use it?”

“No.” Mom’s voice was firm. “We will not use this broom until we check with the peddler. But let’s take it inside so Tony won’t get it.”

“When will Jimmy come again?” Tommy wondered.

“Probably in a few days,” Mom said. “If it his broom, we will give it back.”

What a beautiful broom! How majestic, how straight, how golden! The handle stretched smooth and long from the crisp, honey-colored bristles to the rounded top. The bottom of the broom was smooth and even to catch all the dirt.

A few days later, the clattering noise of the Model T announced the arrival of Jimmy the Fuller Brush peddler. Every member of the family raced out to meet the truck. Mom carried the broom in one hand like the flag of an advancing army.

Tommy fell in step at his mother’s right hand, in the very shadow of that exquisite, honey-colored broom. Tony followed close at Tommy’s heels.

Tommy had always wondered if God really heard prayers. Now he was seconds away from finding out.

chapter two

The Perfect Life

Jimmy lifted his straw hat in astonishment at the sight of the family spilling from the house. Usually, eagerness meant that people had money to spend, but he knew that could not be the case with the Kirkmans.

Mom held out the broom.

“Could you have lost a broom?” she asked. She told Jimmy where they had found it.

“Why, I certainly have not, ma’am,” he said. “Nothing’s been missing from my truck for weeks. If that broom was left beside the road, it’s yours! Can you use it?”

That night, when supper was over and the dishes were washed, the family gathered in the flattened grass outside the front door of the chicken house. Inside, Carol swept the floor thoroughly for the first time since they had moved in.

Mom took a deep breath. “Let’s sing,” she said. Bill brought Dad’s guitar from inside. As the golden sun disappeared behind the treetops, everyone joined in singing Mom’s favorite song. The words swelled to the sky.

“To God be the glory, great things He has done!

So loved He the world, that He gave us His son,

Who yielded His life an atonement for sin,

And opened the life gate that all may go in!”

Tears streamed down Mom’s face as she sang the words. It made Tommy feel like crying too. He wondered if Mom was crying because she was thinking of the blind lady who wrote the song or because they had to live in a chicken house. Or was she crying because God had sent them a broom?

It seemed as if God heard two prayers in a row, because a few days after that, a neighbor came to talk to Dad.

“I’ll make some coffee,” Mom said, hurriedly dipping water from the water pail.

“Oh, don’t worry,” the man said.

“It will just take a moment,” Mom said. “Kirkmans always have coffee.” “Good for you,” the man said. “A whole lot of people are drinking stronger stuff these days. If they can get their hands on it.”

“Not me,” Dad said. “Never. I watched my father kill himself with alcohol. I’ve never touched the stuff, and I never will.”

By the time Dad had been eleven years old, his mother had died in childbirth. That’s when his father, dark with despair at the loss of his young wife, took up drinking. He soon found himself ill with his addiction, finally dying from a bout of pneumonia that most young men would have survived.

The man nodded sympathetically and then got down to the point of his visit. “Doc,” the man said, “there’s forty acres for sale up the road here for $500.” Dad said nothing. If he had $500 to spare, the family would not be living in the chicken house.

“There’s a poplar grove on one side,” the man said. With his finger, he drew a square on the kitchen table and divided it into two lots.

“I have a suggestion, Doc. I’ll loan you the money, then you can build a house there. You know how to build.”

Roscoe did know how to build. He had an engineer’s mind, even though he had only been to school for a few grades. When Dad and his siblings had found themselves orphans, Dad had dropped out of school to make money. While the younger children were sent to live at their grandma’s house in another town about forty miles away, Dad had stayed in Avoca to make money by chopping wood. As he swung his ax, he transformed his teenage muscles into bands of steel.

Yes, Tommy’s dad certainly knew how to use an ax. Tommy had heard the story of his aunt Irene, Dad’s little sister. Dad told it whenever Tommy got in his way and was in danger of getting hurt.

Since her brother Roscoe was her main connection to life before their parents had died, little Irene wanted to beTom’s parents, Roscoe and Bernice Kirkman near him. One day she climbed onto the train close to Grandma’s house and got off in Avoca, where she found Roscoe at his job chopping wood. Roscoe sent his little sister back to Grandma with instructions to stay, but she kept coming back.

Every time it happened, Dad sent word to Grandma to let her know what had happened to Irene. Finally they gave up. If Irene would disappear, they would all just assume she had run away to be with her brother.

The problem with Irene, Dad told Tommy, was that she hindered his wood chopping. She would dart in from behind and put her hand on the woodpile just as Dad was about to swing his ax. His heart would jump up almost to his throat. Finally he took a double spring trap and had Irene sit on it. It was folded open, and every time Irene started to get off, the trap would pinch her. Now Dad could finish his wood chopping, and Irene could watch without getting injured.

This wood chopping and babysitting was the beginning of a life filled with both construction and children. Dad’s reputation for woodwork had made its way around the community, and the neighbor with the forty acres was confident in him.

“Build yourself a log house with those trees on this side of the lot,” the neighbor continued. “Sell off the other twenty acres to pay me back, and then pay the rest as you are able. If it takes twenty years, it takes twenty years.”

Mom was still fussing with the coffeepot and two stoneware mugs, but Tommy could see one side of her face. A tear rolled down her cheek and she pinched her lips together as if she were trying to gain composure. As she picked the coffee percolator off the small burner and began to pour the coffee into the mugs, her hand trembled.

She took the mugs of coffee to the men and then sat down beside Dad with her own mug.

Dad held his mug in his hands and let the steam rise into his face. “You don’t need to do this,” he said.

“Doc, don’t mention it,” the neighbor said. “You would do the same for me.”

The site for the new cabin was just up the road from the chicken house. That evening Dad and the boys decided to go take a look at it. Rabbits and squirrels darted away into the thick woods as they walked. When they crested the next hill, they could see the cabin site not far ahead. It sat at the corner where Trogdon Road turned off toward the town of Needmore, where Tommy’s older brothers and sisters went to school.

The next day Dad, Bob, and Bill began to chop down trees for the new log cabin. When permitted, Tommy, Joe, and Tony joined them. Tommy liked to play with the wood shavings and the log cutoffs that were not used. He listened to the whirr of Dad’s whetstone as he sharpened his knives and axes. As the sides of the log house began to rise, Tommy and Joe played with sticks and small limbs and built miniature log houses of their own. Best of all, Tommy and Tony ran through the grass and stumps around the new cabin. Sometimes they would fall into the scratchy grass and roll around and around. Tony licked Tommy with his scratchy red tongue, his mouth wide open and laughing.

Neighbors traveling up North Pike Road stopped to check on the progress of the Kirkman cabin. Whenever Grandpa Franklin visited, he asked Tommy if it wasn’t about time Tony moved back in with him. Tommy was pretty sure Grandpa was joking, but all the same it made him nervous. He couldn’t imagine being separated from Tony.

Some days, cousin Opal helped the men build. Opal was Bob’s age, and he had a real football made of leather. During break time, or in the evening when the work was done, Bob and Opal practiced spiraling the football in a high arc in the clearing beside the rising cabin. Tommy and Tony watched them. When the ball escaped and careened into the brush, boy and dog tore after it.

Tommy was glad Mom prayed so much. They had gotten the broom because she prayed, and now they were getting a new house too.

The worst was over, surely. Tommy supposed that once they moved into the new cabin, there would never again be sad days.

They finally moved into the cabin and, just as Tommy expected, they were happy. Mom sang and sang, and the whole family joined her in song every evening.

Tommy was seven now and Joe was four. Life was perfect. They lived in a real log house instead of a chicken house. They also had a new baby sister Joan, the cutest person the world had ever known. It was 1941 now and the Depression was officially over. True, the newspapers were filled with stories of war in far-off Europe. But Tommy didn’t know why everybody talked about it so much. After all, they didn’t live in Europe; they lived in America. Tommy was now in second grade, and he was pretty sure he knew almost everything.

It was Sunday afternoon—December 7, 1941. Tommy and Joe lay on the floor by the wood stove. Tommy loved to draw, and Joe tried to do whatever Tommy did. Mostly, Tommy drew solar systems. He drew Jupiter, decorated with many moons; Saturn, with its rings; and Earth, with the continents in blue oceans. On this particular day, Tommy was making a sketch of the tall glass vase from Grandma Franklin.

“This vase was made by a glass blower,” Mom had told Tommy when she carried the vase over on the day they had moved to the chicken house. “Someday we might get a chance to see a glassblower in action.”

Tommy had stared at the vase, trying to imagine someone blowing hot glass. How could someone create glass that looked as if it had grown in the woods?

Tommy studied the vase, trying to sketch it just right. The vase was narrow at the bottom and wide at the top. The top edge of the vase dipped and rose like a road on the side of a hill. When Patsy or Carol cleaned the dust off the vase, their rag went up and down over the edges.

Tommy looked down at his paper, then up at the bookshelf and the tall glass vase. He made the top of the vase wider than the bottom. Carefully he drew in the glass rings that made the vase look like the trunk of a palm tree. The ruffled top almost stumped him. There were not only the ruffles on the near side of the vase, but also those on the far side. Those pieces of ruffle had to be drawn too, or it wouldn’t look right. Tommy sketched and then erased over and over.

Bob and Bill, eighteen and fifteen years old, played a game of checkers on the floor in front of the couch. Thirteen-year-old Patsy sat on the couch above them, playing with baby Joan, and ten-year-old Carol was curled up on the other end of the couch, reading a book. Mom was in her rocking chair, rocking gently to the rhythm of violin music coming from the radio. Dad dozed in his armchair, close to Mom, on the other side of the radio. His feet rested on the brown upholstered footstool Mom had made. Mom didn’t mend clothes or crochet on Sunday, and there was no newspaper. Instead, they listened to fine orchestras from distant places like Chicago or New York.

“We interrupt this broadcast to bring you a special bulletin from NBC,” a voice broke into the music program.

Mom’s eyebrows shot up at the sudden stop of the music and the hurried voice of the announcer.

Tommy didn’t know what it meant to interrupt a broadcast. But he didn’t like the look on Mom’s face. Something was wrong.

From the White House to the Amish winner

I drew a winner from your comments using random.org. That person is:

Comment #67, Marilyn Brown

Congrats Marilyn. Please forward me your address to ewesner[at]gmail[dot]com to have your book sent out courtesy of Katrina.

Where to get the book

If you didn’t win, Katrina explains where you can get the book:

I encourage readers to buy directly from my website if they are able, since that supports my own author journey best. I send autographed paperbacks directly from my house in Elkhart, IN. The paperback, ebook, and audiobook can all be purchased directly from me here.

However, the ebooks are available on Apple, Nook, Amazon, and more; you can see a list of the retailers here. The paperback is available from Amazon, but it will be more expensive than if you buy it directly from me. We recently released the audio version with narration by Conrad Bear. This can be accessed from our website as a digital download or a CD set. Also available from Apple, Audible, Nook, Kobo/Walmart, and various others.

There is also a discount code for Amish America readers:

If you purchase from my website, don’t forget to use coupon code Amish15 for 15% off any form of From the White House to the Amish (paperback, ebook, audiobook).

Thanks to Katrina for sharing her book with us, and for this great promotion.

Congratulations, Marilyn!

Lucky you!On

I read the excerpt from the book and am hoping to purchase it. I’ve been reading many books set in WWII this past year, figuring if my parent’s generation could survive the great depression and the war, we can survive this pandemic! I’m interested to find out what happens to Tommy’s family as the U.S. enters the war.

I hope everyone is doing the best they can and that brighter (and warmer! It’s in the single digits as I write this!) days aren’t too far off!

Alice Mary